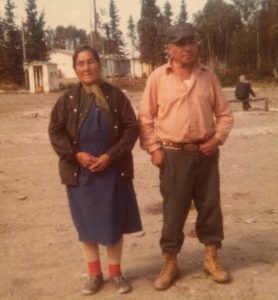

Sihkos’ Story, Part V: Portrait of My Parents

Jane Glennon (Woodland Cree), B.A., B.S.W., M.S.W., is a retired social worker, counsellor and teacher who currently lives in Prince Albert, SK. This is the fifth in her series of writings for MI about her time at residential school and beyond. Here, she shares recollections of her parents.

(Click to enlarge)

I was not the first in my family to attend residential school. My mother was also a survivor, a journey that began when she was orphaned at a young age.

Nikâwiy — the Cree word for ‘my mother’ (pronounced nih-GAH-wee) — was a woman of medium height who tended to be a little overweight. I recall one of my father’s friends saying that my mom’s fine features made her very pretty, and that she was just the right size when she was young. Although two of nikâwiy’s five daughters inherited her chiselled nose, none of us had her beautiful, soft curly hair.

Nikâwiy may’ve only had a grade six education, but she had a passion for reading. She used to read us stories from a Readers’ Digest. Her favourite material was stories of romance: I suspect it had something to do with her being orphaned, and how that seemed to determine her fate in life as a wife and a mother.

However, I do know that she sought more for herself. People from the reserve who admired her love of literacy used to ask her to write and interpret for them. She once thought about running as a Band Councillor. But my father — who was illiterate, and spoke only some English — was against it, and that was that. I thought that was totally unfair.

My parents had a complicated relationship right from the start. It was not until later in life that I learned that, prior to marrying my father, my mother had a daughter with another man. But she and this man were not allowed to be together, and their baby (the sister I never met) would end up adopted by a family from another reserve. I also learned that my parents’ marriage was an arranged one, taking place not long after my mother left school. My mother breathed not a word of these early experiences to her sons and daughters.

Thinking back over these aspects of her life, I now realize why we never got a hug or heard an “I love you” from our mother. To the day she died, my mother was not openly affectionate with any of us. (I’m sad to say that, as a parent, I never showed overt affection toward my children, either: a truly inter-generational impact of residential school.) That said, I must admit nikâwiy did try to show her feelings in other ways, and, even though some of us were a challenge, we all knew she truly cared for her family.

Other enduring memories of my mother include her skills as a cook, skills she never passed on to us girls. I used to marvel at how terrific her bannock was, and wonder how she learned to make such delicious rice pudding. Speaking of pudding, her Christmas version, with its scrumptious white sauce — ‘la pudgin,’ we called it — was fabulous. My mother also made the most delightful fish soup, which closely resembled clam chowder.

Using an old-fashioned sewing machine, my mother sewed all her own dresses using colourful prints. She also made beaded moose hide moccasins for us kids. But when I brought mine to school, I was forbidden from wearing them.

Nikâwiy neither drank nor smoked, although she secretly liked to chew snuff (my father forbid it). Devoutly religious after her conversion to Catholicism, she tried to instil such convictions in her children. Discipline consisted of verbal cautions and words of advice whenever we misbehaved. She hardly ever resorted to physical means: I remember how shocked I was the one and only time my mother hit me, whacking my lower extremities with a piece of wood after I’d gotten home very late one night.

Nikâwiy used to tell us stories with a moral to them, often through the exploits of the Cree trickster, Wîhsakecâhk (also spelled as ‘Weesakayjac’ and ‘Weesageechak’, it’s pronounced ‘wee-SAA-gay-CHAAK’). Hoping to impress upon us the value of always being prepared, she spoke of how a careless Wîhsakecâhk set off on a journey without proper food or clothing. When he eventually got hungry and cold, he built a fire with some matches he’d packed. But not getting warm enough fast enough, he took a stone out of the flames and sat on it, with predictable results. Now scorched and starving, he went off in search of something to eat.

Some time later, a weary Wîhsakecâhk noticed how the skin on his legs had become dry and scabrous. Desperate, he started to pick at the scabs. By this point, all the animals of the forest were closely observing this increasingly pathetic figure, laughing at his antics. They began to sing, “Wîhsakecâhk is eaaaaating his scaaaabs!!,” which made him feel ridiculous and ashamed. It was definitely one of your more amusing morality tales.

Another of my mother’s stories motivated us girls to faithfully carry out our chores when she said any dirty dishes left overnight would entice the Devil himself to come and do them for you! When we were still quite young, my siblings and I loved to stay out late playing and wait for the northern lights. My mother used to say that they would come down and grab us up. When we whistled at those lights, we’d hear a swishing sound, imagining their approaching nearer and nearer. We sure hightailed it into the house then! You could say this was another way nikâwiy had of disciplining us.

Our mother was just 67 when we lost her to kidney cancer, but her memory lives on through her children, and through the grandchildren she helped rear.

* * *

Known by his nickname Nâpew, which means ‘the man’ in Cree, my father was a handsome and hefty man who had a way with the ladies. Indeed, he always managed to have his coarse, jet black hair cut neatly by one of the local barbers. He liked to dress just as neatly, and I used to love watching him shave every morning. (Which reminds me of a funny story: back when I was a young woman and loved using make-up, nohtawiy mistook one of my face creams as an aftershave. He quickly learned it was much too oily and had a hard time washing it off!)

Nohtâwiy (‘my father’ in Cree, pronounced noh-TAA-wee) was a good provider. With his stoutness came great strength, so, when he was young, dad worked on a large craft similar to the York boats, hauling supplies up and down the Saskatchewan River. He was later assigned a trap line around Southend, our reserve. An excellent trapper of beaver, muskrats, mink, weasels and squirrels, he was also a good hunter of moose and deer. Summer allowed my father to earn an adequate income in commercial fishing.

However, there were lean economic times too, and with as many as eleven mouths to feed, it meant nohtâwiy occasionally faced difficulties fending for the family. Though we went hungry then, we always managed to stay warm in our cozy home.

My parents rarely used physical forms of discipline on us children. But there were those times when someone faced some extreme convincing by my father’s strong hand. One incident I particularly remember involved a younger sister who, like most teenagers, was restless and rebellious. She had constantly been late in coming home, sometimes not even coming home at all. When things came to a head, I remember thinking my father right at the time for choosing to impart some harsh discipline.

* * *

Before the road to our reserve was built, the only way in was by plane. When I was growing up, there were no school or health centres; medical and other government personnel came in periodically. Then came the road, and it was like a dam had broke. Although it brought positive changes to the community, this new route also made it easier for the negative influences of alcohol (and, later, drugs) to enter.

Big changes to the reserve seemed to precipitate equally big changes in my father. He began to drink more often. Back when Southend was still isolated, the only way to get wine was to order it in by mail, which came every two weeks by plane. In between, the older men of the reserve like my dad used to make home brew, a thirst they seemed to quench in a more or less quiet and peaceful way amongst themselves.

But with the reserve no longer so remote, many men now obtained booze through bootleggers or else hired someone to buy it for them whenever they drove to town. Soon after, the women and youth also started to drink, which totally changed the equation for families; for some, alcohol became their main priority. Children became neglected and abused, women mistreated and beaten.

My father appeared to be washed along by this flow of misguided family values, and his drinking habits would increase over the years. The times I was at home, I never witnessed any abuse against my mother or my siblings. But that doesn’t mean the bottle did not affect their lives. It did so well into adulthood, some even to the point of death.

But it is not for me to sit here in judgment of my father: I do not mean to imply that he taught his children how to drink. At that time, there were no organized recreational activities for young people; at best, a few were kept occupied by seasonal employment. Then, when welfare came along, it seems to me far too many young people chose to go that route instead of bettering themselves through meaningful employment outside the reserve.

My father later became afflicted with dementia. It got progressively worse, right until his passing at the age of eighty-seven. I was there at the hospital to share his final night, and was happy to do so. Nohtâwiy always had endearing and encouraging words for me, and I loved him dearly.

Thank you for your stories. Your parents sound like wonderful people.